|

| Georges Seurat View of LeCrotoy 1889. Private Collection |

Physical Reality and Human Perception

This module sets the philosophical tone of the rest of the course.

Whilst we are deep in erudite discussion of the workings of nature and

the physical origin of things like rainbows, we should keep in mind that

everything is illusory, not real, a construction of whatever in our

brains creates consciousness. Vision, like physics, is only a model

of reality and is subject to unconscious social and biological forces.

The senses

The Illusion of mind

All neurons speak the same sylables

The language of vision

Vision is a Map of Reality

(with typographical errors)

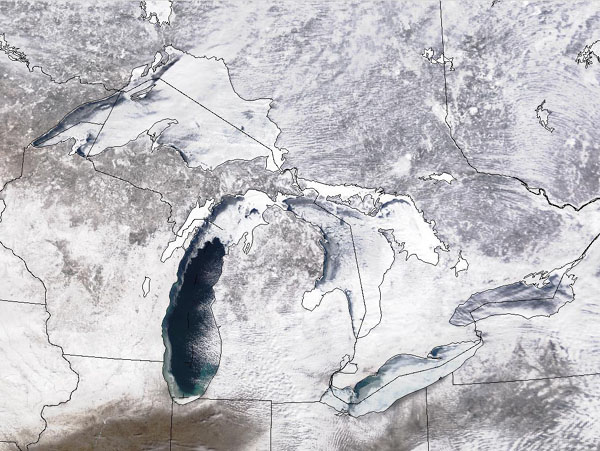

The photograph shows ice, snow, clear water, and various land surfaces.

We know which is which in the picture.

However, what you are looking at is just a series of glowing pixels

on your monitor; it is NOT ice, snow, clear water, and various land

surfaces.

The white areas correspond to ice and snow, etc.

On a map, lakes are nearly always represented with blue ink;

they are not actually little wet lakes on the paper.

Vision also is only a map of the outside world.

Our consciousness has developed a sequence of conventional "inks" that

always (or nearly always) have a one-to-one correspondence with outside

phenomena.

These representations have hidden implied conventions built into them,

like the blueness for lakes on a map.

A postmodern philosopher might tell you that the conventions are as much

a product of social history as they are "hard-wired" into the neural

processing.

Be that as it may, maps and photographs leave things out.

They do not taste, smell, feel, or sound like the 'reality' they represent.

They do not include details of three-dimensional shape and texture.

They don't change with time.

What has our vision left out?

How would we know?

Physicists have all sorts of experiments for measuring properties that

our senses are not aware of, but in the end, the results are always

described in terms of sensual perception, like shape, mass, and force.

Pattern recognition.

Due to the camera viewpoint, the rectangles are distorted into a trapazoids with

angles that do not equal 90°.

On your retina, the image shapes are further deformed into curved lines.

Yet, we have no trouble recogizing the architectural purity of the rectangles.

Scientists have recently found that we have very specific cells in the brain

that respond to very specific objects in our view.

This finding might not be surprising for very familiar objects like family

members.

But individual cells even respond only to yellow houses and nothing else.

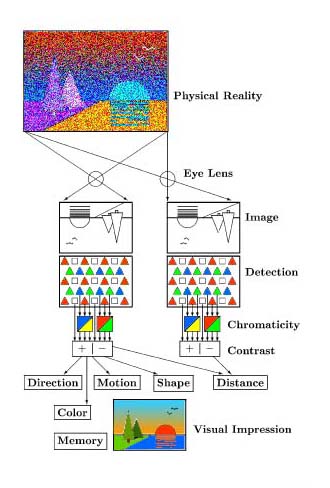

The Visual Path

All we know about consciousness is that it

appears to be distributed over all the feedback loops of the brain.

Some speculations about the animal kingdom

InDepth:

Synesthesia

Sample questions for reflection:

How do the senses communicate with the brain?

Why is vision an illusion?

What properties does vision assign to objects?

How are maps like vision?

Consider Seurat's picture above.

What is the goal of vision?

What are the main steps along the visual path?

What is synesthesia?

All our senses translate different stimuli from the external

world into similar electro-chemical pulses running from nerve

cell to nerve cell into the brain.

Hearing

converts air oscillations into nerve pulses by waving tiny hairs

in the cochlia of the ear.

Taste

converts chemical reactions into nerve pulses on the taste buds of the

tongue.

Smell

converts molecular shape into nerve pulses in olfactory bulbs in the nose.

Touch converts

pressure

and

heat/cold

into nerve pulses by receptors in the skin.

Vision

converts light into nerve pulses on the retina.

All senses are body receptors; the mind creates the illusion of an

external world.

We do not in any way directly experience or know the character of

physical reality.

Wetness is a concept invented by consciousness to remember the feeling of

liquids.

All the aspects of vision are similarly invensions of consciousness.

We imagine the external world only from a strange stimulus on the

retina.

In effect, Seurat is telling us in the picture above that sailboats do not

exist; there are only atoms and photons, neither of which have color or

shape.

The sailboats are constructions of consciousness devised by billions of years

of evolution to represent memorable objects.

What is the character of the color orange?

Can you explain orange to anyone else without referring to orange objects?

Much of this course discusses the biophysical processes which contribute to

the construction of the visual experience.

Later there is an InDepth module on optical illusions.

Optical illusions are picture "tricks" designed to confuse your vision

system.

However, every vision is an illusion; some, like oceans and sailboats,

are just more consistent than others so we think they are 'real'.

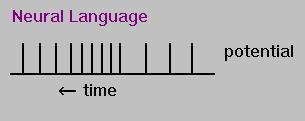

Imagine these electro-chemical pulses traveling from neuron to neuron

to the right.

The brain receives the right pulses first, and then later the left pulses.

Each pulse is nearly identical.

A stronger stimulus, (e.g. brighter light) makes the pulses come

at a higher rate.

The interpretation depends on where in the brain the pulses go.

Visual pulses eventually get to various parts of the visual cortex.

Objects imagined by consciousness have four seemingly independent

characteristics.

Each is processed in a different part of the visual cortex.

It is easy to think of these characteristics, but it is hard to imagine

separating them and analysing them in different parts of the brain without

reference to the object itself.

The brain does this separation before it has developed a concept of

'object'.

Now, we might ask: do objects have these characteristics precisely because

they are analysed in different regions of the brain, and consciousness constructs

representations from these building blocks, or do they really have these

characteristics and nature has found clever ways of teasing them out for analysis?

Most scientists favor the latter, but that might just be because they are still

in the 18th and 19th centuries of the enlightenment period.

One way to think of vision is to consider the relation between a map

or a photograph and the "reality" it represents.

Here is a photograph of the Great Lakes region in winter.

The most important biological function of vision is pattern recognition.

We recognize the ice and Great Lakes in the picture above because we have

seen these patterns before.

Pattern recognition obviously has survival value.

Our eyes are designed to find apples, tigers, and mates, under all

circumstances of point-of-view, lighting, shadows, partial concealment,

and a hundred other variations.

Our most important experiences come from other humans.

Our ability to read even very subtle facial expressions and hand gestures

is exquisite.

Engineers spend whole careers designing pattern recognition hardware and

software for machine vision.

These pages contain several modules about how our eyes do it.

Look around the room you are in right now.

I am sure it contains many recognizable rectangular shapes, like

doors, windows, framed art or photographs, the walls themselves.

But, none of these features present a true rectangle to your point of

view.

You can check out the non-rectangleness by holding up a card face-on to

to you in front of any of the shapes.

Here is a photograph of a window.

Here is a diagram of the information path from object, to perception, to

conscious construction:

We can pretty much follow the information path all the way to this point.

Somehow all the processed data from the various areas of the visual

cortex is blended with memory in the hippocampus of the brain.

Then the miracle happens.

All vertibrates and many species of other phyla have eyes similar to our own.

It would not be a surprise to find that all such animals create similar

world maps.

Almost without saying, a self-constructed map with the observer at the center

implies a sense of self.

It is probable that consciousness is a characteristic of all forms of life

to a greater or lesser degree.

Even plants and bacteria interact actively with their environment.

Such interaction suggests a decision-making process, even if it is only chemical.

Maybe our decisions are only chemical.

As many as one in every 1,000 people have

sensory experiences in which a visual,

auditory or other stimulus also prompts an

experience with another of the five senses.

That is, some people "see" sounds, "taste"

shapes, or "feel" colors, and these sensations

are as real to them as any so-called normal

sense perception.

What form do the signals on nerve cells take?

How many 'layers' of representation are present?

What are you actually looking at?

Given the information about our senses described above, how might it come about?